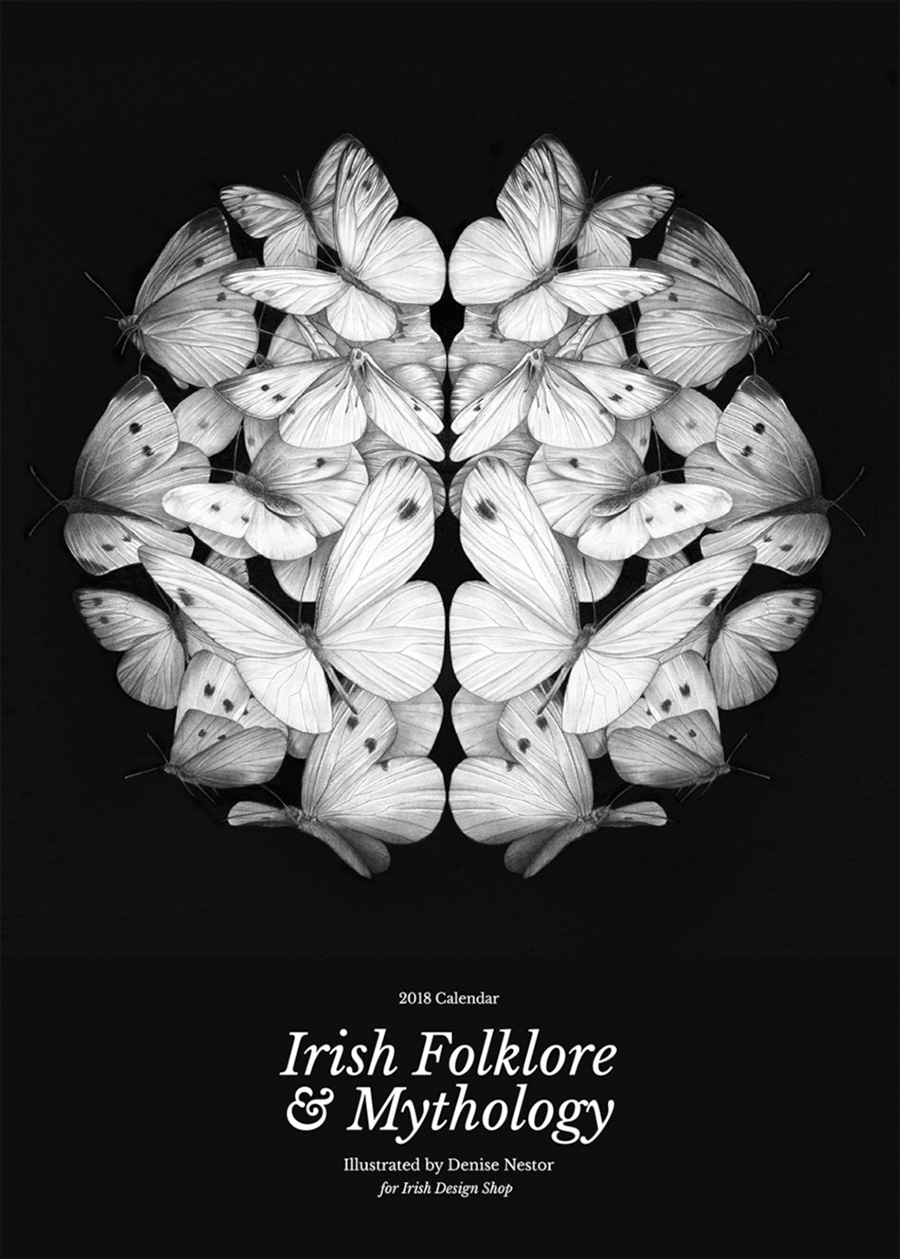

A print collection calendar illustrated for Irish Design Shop, inspired by Irish folklore & Mythology.

(Descriptions below)

The Werewolves of Ossory

Aengus Óg

Faery Birds

The Horned God

Foxgloves

The Sons of Tuireann

Chasing Rabbits

The Púca

Dealán Dé

Wren Day

Descriptions:

'The Werewolves of Ossory'

Ossory was an old kingdom of Ireland, now comprised of Kilkenny and Laois. There have long been stories about werewolves associated with this region. 'Cóir Anmann', a 12th century manuscript, offers an account of a man named Laignech Fáelad, said to be an ancestor of a tribe of werewolves who were related to the kings of Ossory. According to the 'Cóir Anmann', ‘he was a man that used to go wolfing, into shapes of wolves he used to go, and his offspring used to go after him and they used to kill the herds after the fashion of wolves, so that it is for that that he used to be called Laignech Fáelad, for he was the first of them who went into a wolf-shape’.

Legend has it that when St Patrick preached to groups about Christianity, Laignech and his followers howled like wolves in protest in order to drown out his voice.

Ossory was an old kingdom of Ireland, now comprised of Kilkenny and Laois. There have long been stories about werewolves associated with this region. 'Cóir Anmann', a 12th century manuscript, offers an account of a man named Laignech Fáelad, said to be an ancestor of a tribe of werewolves who were related to the kings of Ossory. According to the 'Cóir Anmann', ‘he was a man that used to go wolfing, into shapes of wolves he used to go, and his offspring used to go after him and they used to kill the herds after the fashion of wolves, so that it is for that that he used to be called Laignech Fáelad, for he was the first of them who went into a wolf-shape’.

Legend has it that when St Patrick preached to groups about Christianity, Laignech and his followers howled like wolves in protest in order to drown out his voice.

'Aengus Óg'

Aengus Óg was a member of the Tuatha Dé Danann, an ancient tribe of gods and goddesses from Irish mythology. In time they became known as the Aos Sí (people of the sidhe), and in later folklore were known more familiarly as ‘the faeries’.

Aengus Óg was the god of love and poetic inspiration and it was said that everywhere he went, four little birds hovered above his head. They were said to have been formed from his kisses and carried messages of love.

Aengus Óg was a member of the Tuatha Dé Danann, an ancient tribe of gods and goddesses from Irish mythology. In time they became known as the Aos Sí (people of the sidhe), and in later folklore were known more familiarly as ‘the faeries’.

Aengus Óg was the god of love and poetic inspiration and it was said that everywhere he went, four little birds hovered above his head. They were said to have been formed from his kisses and carried messages of love.

'Faery Birds'

The arrival of the barn swallow in April is commonly believed to mark the beginning of spring. For centuries, before people understood that certain birds migrated for winter, there were strange theories as to why they magically disappeared and then reappeared each year. Many people believed that these were enchanted birds, associated with the faeries, and that they spent the winter months in the Otherworld. It was even thought that they shape-shifted into other birds.

Because swallows were often seen flying low over lakes, some people believed that they disappeared under the water and stayed hidden there, only to emerge again the following April.

The arrival of the barn swallow in April is commonly believed to mark the beginning of spring. For centuries, before people understood that certain birds migrated for winter, there were strange theories as to why they magically disappeared and then reappeared each year. Many people believed that these were enchanted birds, associated with the faeries, and that they spent the winter months in the Otherworld. It was even thought that they shape-shifted into other birds.

Because swallows were often seen flying low over lakes, some people believed that they disappeared under the water and stayed hidden there, only to emerge again the following April.

'The Horned God'

In Celtic terms, the stag represented the renewal of nature and the fertility of the forest. Understood more generally as a symbol of the natural world, the stag was dangerous but also benign and beneficial. Cernunnos was the Celtic god of fertility, animals, wealth and the underworld. Sometimes depicted as a man with antlers, he was referred to as ‘The Horned God’.

In Celtic terms, the stag represented the renewal of nature and the fertility of the forest. Understood more generally as a symbol of the natural world, the stag was dangerous but also benign and beneficial. Cernunnos was the Celtic god of fertility, animals, wealth and the underworld. Sometimes depicted as a man with antlers, he was referred to as ‘The Horned God’.

‘Foxgloves'

The foxglove has a long association with both foxes and faeries. A potion made from the foxglove plant was said to be able to break a faery spell and restore changelings to true children. There are various theories about where the name ‘foxglove’ originated. One theory is that it is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ‘foxes-gleow’, ‘gleow’ meaning a ‘ring of bells’. It was believed that the faeries taught foxes to ring the foxglove bells, so that both would be warned of approaching hunters. Another theory is that the faeries taught foxes to wear the foxglove bells on their feet, so as to soften their steps while hunting.

The foxglove has a long association with both foxes and faeries. A potion made from the foxglove plant was said to be able to break a faery spell and restore changelings to true children. There are various theories about where the name ‘foxglove’ originated. One theory is that it is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ‘foxes-gleow’, ‘gleow’ meaning a ‘ring of bells’. It was believed that the faeries taught foxes to ring the foxglove bells, so that both would be warned of approaching hunters. Another theory is that the faeries taught foxes to wear the foxglove bells on their feet, so as to soften their steps while hunting.

'The Sons of Tuireann'

Tuatha Dé Danann, avenges his father’s death by tasking the three

sons with gathering magical weapons, which Lugh plans to use at the Second Battle of Magh Tuireadh. In return for succeeding in these perilous quests, they will be granted mercy. For one of these tasks, Tuireann turns his three sons into hawks so they can steal golden healing apples from an orchard. The king who owns the orchard orders his men to attack them with spears but they manage to escape. In the end they succeed in obtaining all that Lugh demanded, but return badly wounded. They plead for Lugh to heal them but he refuses. The three sons die and Tuireann dies of grief on their graves.

Tuatha Dé Danann, avenges his father’s death by tasking the three

sons with gathering magical weapons, which Lugh plans to use at the Second Battle of Magh Tuireadh. In return for succeeding in these perilous quests, they will be granted mercy. For one of these tasks, Tuireann turns his three sons into hawks so they can steal golden healing apples from an orchard. The king who owns the orchard orders his men to attack them with spears but they manage to escape. In the end they succeed in obtaining all that Lugh demanded, but return badly wounded. They plead for Lugh to heal them but he refuses. The three sons die and Tuireann dies of grief on their graves.

'Chasing Rabbits'

Rabbits have long been associated with faeries in Irish folklore. It was believed that rabbits burrowed underground to better commune with the Otherworld, and that they could carry messages from the living to the dead and from humans to faeries. There are many stories in Irish folklore about people encountering a rabbit late at night. Falling under a spell, these people were compelled to chase the animal and, upon returning home the next morning, discovered that several years had passed.

The fly agaric, the iconic toadstool mushroom of childrens’ stories, was also associated with the faeries and the Otherworld. It is most likely that this connection was to do with the psychedelic hallucinations that people experienced after eating them.

Rabbits have long been associated with faeries in Irish folklore. It was believed that rabbits burrowed underground to better commune with the Otherworld, and that they could carry messages from the living to the dead and from humans to faeries. There are many stories in Irish folklore about people encountering a rabbit late at night. Falling under a spell, these people were compelled to chase the animal and, upon returning home the next morning, discovered that several years had passed.

The fly agaric, the iconic toadstool mushroom of childrens’ stories, was also associated with the faeries and the Otherworld. It is most likely that this connection was to do with the psychedelic hallucinations that people experienced after eating them.

'The Púca'

The Púca is a malevolent faery that can shape-shift into different forms. It often appears as a black horse and is sometimes seen as a dark animal that resembles a hare or a rabbit with glowing eyes and long black hair. It is most often seen at night, sitting silently on the branch of a tree. It is said that you shouldn’t eat blackberries after the 31st of October because the Púca covers them in spit on Hallowe’en Night.

The Púca is a malevolent faery that can shape-shift into different forms. It often appears as a black horse and is sometimes seen as a dark animal that resembles a hare or a rabbit with glowing eyes and long black hair. It is most often seen at night, sitting silently on the branch of a tree. It is said that you shouldn’t eat blackberries after the 31st of October because the Púca covers them in spit on Hallowe’en Night.

'Dealán Dé'

The old Irish name for the butterfly was ‘Dealán Dé’, meaning ‘light of the Gods’, but the origins of this name are unknown.

It was believed that butterflies were connected to the Otherworld and that they could pass freely between this world and the next. Butterflies were thought to carry the souls of the dead to the Otherworld, while white butterflies carried the souls of children. For this reason they were treated with respect and reverence and it was seen as bad luck to harm them.

The old Irish name for the butterfly was ‘Dealán Dé’, meaning ‘light of the Gods’, but the origins of this name are unknown.

It was believed that butterflies were connected to the Otherworld and that they could pass freely between this world and the next. Butterflies were thought to carry the souls of the dead to the Otherworld, while white butterflies carried the souls of children. For this reason they were treated with respect and reverence and it was seen as bad luck to harm them.

'Wren Day'

Wren Day is celebrated on the 26th of December, St Stephen’s Day. The tradition consists of ‘hunting’ a wren for use in a ritual that can be understood as either sacrificial or celebratory. In the past, a live wren was caught and placed in a cage, however in later years a fake wren was made with feathers and sticks and tied to a pole decorated with ribbons and holly. Young children would go from house to house with

the wren, reciting the rhyme: “The wren, the wren, the king of all birds / St Stephen's Day was caught in the furze / Up with the kettle and down with the pan / Give us a penny to bury the ‘wran’.”

In Celtic mythology, the wren was considered to be a symbol of the past year and the celebration may have been a midwinter sacrifice, welcoming the new year. The wren is often referred to as the ‘Druid bird’ and old Celtic names for the wren mean ‘druid’. This further links it to druidic practices; a possible source of the ritual of wren day.

Wren Day is celebrated on the 26th of December, St Stephen’s Day. The tradition consists of ‘hunting’ a wren for use in a ritual that can be understood as either sacrificial or celebratory. In the past, a live wren was caught and placed in a cage, however in later years a fake wren was made with feathers and sticks and tied to a pole decorated with ribbons and holly. Young children would go from house to house with

the wren, reciting the rhyme: “The wren, the wren, the king of all birds / St Stephen's Day was caught in the furze / Up with the kettle and down with the pan / Give us a penny to bury the ‘wran’.”

In Celtic mythology, the wren was considered to be a symbol of the past year and the celebration may have been a midwinter sacrifice, welcoming the new year. The wren is often referred to as the ‘Druid bird’ and old Celtic names for the wren mean ‘druid’. This further links it to druidic practices; a possible source of the ritual of wren day.